I had the chance to see Claire Burbridge‘s exhibition at the Nancy Tomey Fine Art Gallery, one of the best galleries of Minnesota Street Project, just few days before its closing. It has been a magic serendipity, in fact Burbridge’s Night Garden gathers all that I dream of: wandering in an evergreen valley without searching for anything, where the perfection of Nature stands alone, and so do I. Claire Burbridge’s works also gathers all that I pursue in my artistic practice: line, a vibrating palette, care.

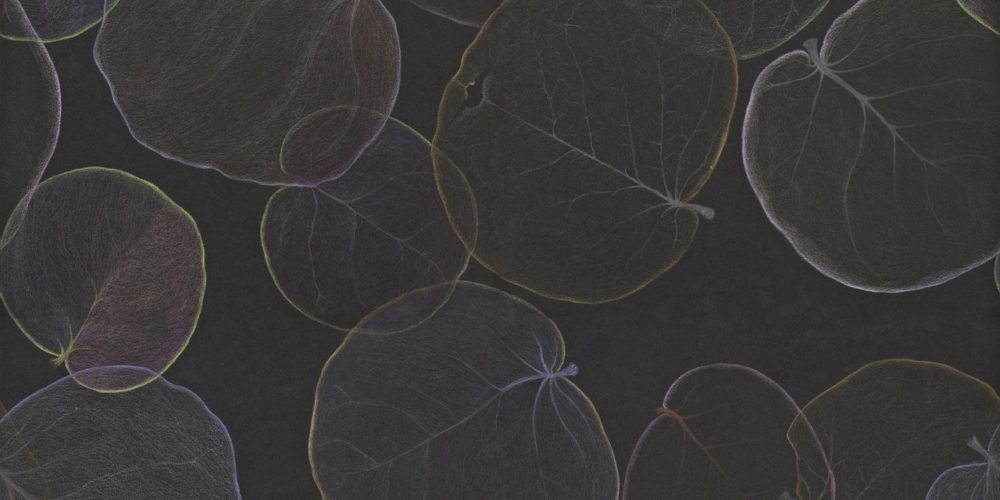

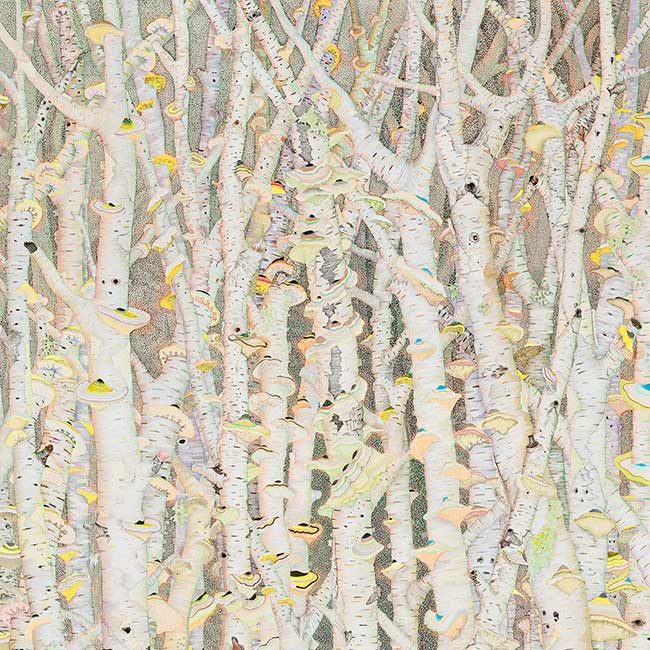

It seems that we share the same obsession for floral beauty, but if my reverence for it doesn’t even allow me to portray it, Burbridge is able to reproduce it on wallpapers and on large scale posters —as leaves, mushrooms, petals, stalks, minuscule living organisms—which creates landscapes, the perfection of which can’t be compared to anything else but to that of a self-sufficient ecosystem. In this case the floral beauty is not simply portrayed by the artist, like in a hyper-realistic painting, but instead is given new qualities that are achievable only through the immense care of the artist. By “care” I mean patience, focus, tenacity, respect for the artistic subject, the technique and the tools used.

As she explains in the interview for Imagination International, Claire Burbridge’s aim is for the viewer to sense “the connectedness and cyclical nature of life, and the universe”, and I certainly confirm that she succeeds. It’s really easy to get lost in the intricacies of ink, pastels and markers (apparently she loves the Copic markers in particular). Staring at the meticulous drawings does give you the sense of connection, first of all with the artwork and secondly with the subject represented: Nature.

About her exhibition for the Nancy Tomey Burbridge says: “Each drawing is a natural evolution from the last. I work for about a year immersed in a particular subject, watching it evolve through the seasons. Although I learn a lot about the subjects of my drawings, the facts are not a dominant feature. These are not strictly botanical illustrations. Through the handling and observing of the forms, information reveals itself to me in wordless fashion. My studio is now home to many dried fungi, lichens, dead insects and bits of trees. These all fascinate me as they continue to change through the process of decay. I am particularly interested in small forms, like mushrooms, because they exemplify the multiplicity and complexity of nature; hidden, as they are, beneath the earth for most of the year. I strive to depict a vibrant universe, one that speaks of forms decaying, from which new organisms emerge.”

The media used, ink and markers, oblige Burbridge to face the challenge presented by slip ups and other mistakes. All of these little technical oversights led her to develop a unique style, based on the transformation of imperfection into beauty. Despite the extremely tangled figures that overlap themselves in a cascade of colors, the cohesive structure of the images is clear. The order of the compositions is given by the interlocking circles drawn beneath the forms, a pattern mirroring the underlying balance and cycles of natural ecosystems. In Burbridge’s work the understanding of nature comes before its representation; in this sense, thinking of her artistic process, Joseph Albers’ words come back to my mind.

During his years at the Black Mountain College from 1933 to 1949, Albers promoted a teaching method based on experimentation as a form to test reality and to improve it. For Albers teaching art corresponded to teaching students how to master social practices, in order to upend them if necessary; for this reason Art and Ethic are strictly conjoined in Albers’ vision. “Art is both an intuitive search for and discovery of form, and the knowledge and application of the fundamental laws of forms.” Regarding the idea of form, Albers distinguished between matters and materials, referring to the aesthetic qualities of a media with the first term, and to the actual structure of it with the second one. Only once the deep understanding of a material’s intrinsic qualities is achieved, is it possible to use it in the best possible way, expanding its potentialities and at the same time remaining fully respectful of the medium.

Albers adds that “The purpose of Art is to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known. The technique of Art is also to make objects ‘look unfamiliar’, to make forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and length of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged”.

Claire Burbridge connects herself to Alber’s thought through the attentive observation, study and elaboration of biological micro-organisms. Using Albers’ words, we could say that the wallpapers and posters are the visual equivalent of Nature, as a material, and that through the talented drawing the artist makes Nature look unfamiliar, and so forces us to observe it with a process prolonged compared to the time that we usually spend in looking at things, at what surrounds us.

The profound respect for natural eco-systems is visible in the way with which Burbridge lays down little found objects, one close to another on a table, part of the exhibition at the Nancy Tomey Art Gallery—a display of raw jewels showing the auto-sufficient beauty of Nature. Thin roots, dry plants, grass, musk, fungi and rocks represent themselves in all their diversity, yet are offspring of the same Mother.

Against the wall at the bottom of the small gallery, on the floor, an open suitcase gathers more relics of the artist’s pilgrimage in the woods, this time arranged next to a thin book, a couple of photos and personal objects.

Looking at the suitcase and at the organic fragments, collected from different lands and brought into a “white cube gallery”, spontaneously leads me to think about other artists who did the same, such as Cildo Meireles, Maria Rebecca Ballestra (in particular I’m referring to 1kg of investment in Knowledge), Richard Smithson, just to name some of them, all artists whose work revolves around the relationship between man and nature.

Without disturbing references to the Land Art and to the Post-human art practices, that would open a consideration too broad for this article, I’ll just limit myself to say that Claire Burbridge is a 2.0 Land Artist, working at a close distance with the land without getting her hands dirty. Certainly she explores, touches and manipulates the ground, stealing what she needs for creating magical compositions, but her relationship with nature is much more balanced than the one of the properly named land artists of the 60s-70s. The tracks of her passage into landscape are all for us, gallery visitors; they are ink and marker woods to inspect with astonishment, outlines and transparencies that recall souls of fallen Autumn leaves, multi-colored dots of well organized universes revealing to us that we’re nothing but other dots.

Claire Burbridge is one of twins born in London in December, 1971. She grew up on the west coast of Scotland and in rural Somerset where she attended Wells Cathedral School. On leaving she studied for a BA in Fine Art and history of Art at Magdalen College, Oxford before returning to her birthplace to study printmaking at Camberwell College of Art where she gained a Masters Degree. She lives in Oregon with her husband the artist Matthew Picton and son Maurice.